MUSINGS OF A MILITARY MAVERICK- FROM CRADLE TO COMMISSIONING

by Lt Gen YN Sharma

It was a special day at the engineer’s residence, in the premises of the power house. A son—the first-born of the first-wife of the power parivar—had been born. Few newborns can hope for a better beginning; a celebrity father (publicly anointed as the Sun of Muzaffarabad), two doting Mothers (real-sisters) and a silver katora, in lieu of a spoon. As per folklore, that katora became such a trademark that all works would shut down if it went missing. Raja-beta would refuse to drink milk without it.

The rasoi report about the new ‘bundle in the cradle’ was that it had an oversized head and short legs. The former was celebrated as a cerebral future but the latter disturbed the engineer-father. He kept checking, with a slide-rule, whether the design defect was a disability or deformity. No one suspected then, or later, that the Infant would grow up to be an Infantryman, a Ranger-Commando and a General with a game-leg. Does the beginning ever reflect the end? Hardly. It is all in the DNA and destiny both of which are unpredictable and beyond our control.

But it is also said that genes don’t lie. If so, a reality-check of the preceding generation may serve a purpose. The freshly famous father was from an average agricultural-class family. The forefathers had owned land in the hills near Mansehra in Hazara District of erstwhile NWFP. They needed to supplement income, so they arranged logistic-support for the British forces fighting the Afghans; and while so doing often accompanied Army columns. Thus survival in a harsh and hostile environment was their staple, and it paid-off at the time of the bloody Partition.

The mothers’ were raised in a conservative family of Haripur. As was typical at the time and place, they were steeped in tradition and raised to run a home and bring up families, as literates-own-language only. All the education and enculturation was done at home in the absence of schools for girls. There may have been no equal-opportunity for girls in the outside world but at home shakti-power was the ruling deity. And women guarded their ‘space’ jealously, even aggressively, despite the feudal-paternal nature of Frontier-Punjabis. While we may never revert to those times but in it, there are lessons to be drawn about clarity of roles and management of space in relationships.

Our only grandparent who overlapped with us was the charismatic Nana-ji (mother’s father). He was a ‘gentleman of class’—English-educated at Abbotabad (lately of Osama fame); a war veteran (joined Forest service, on demobilisation); a certified Scout-master and a freedom-fighter (a closet-supporter of Germany for the same reason as Neta-ji). At six-foot plus, he was a formidable figure, be it in western clothing or as a gun-toting Pathan in Frontier style. He felt fully fulfilled when my son was commissioned as an officer. Coincidentally, Nana ji was cremated the day after. And Despina and I had gone with celebratory sweets when he was being wheeled out for his last ride.

I faintly recall our Nani. She did not keep good health and passed away in my infancy. I learnt later that as treatment for chronic pain the local quack had got her addicted to an opiate-drug, a pet produce of Afghanistan. The habit became irresistible and she became a prescription-addict. It is hard to tell whether it was this, or the soma-guzzling tradition of our ancients, that was the origin for the family fondness for overindulgence. But it was a generic-mutation as it went beyond my maternal lineage. More than a few siblings, cousins and nephews have seriously succumbed to such temptations.

Perhaps our place of ‘domicile’ played a part. How did we get to be in this remote tribal corner of the North-West? Hazara had been at the crossroads and a stamping ground of many powers and people. The Bactrian-Greeks, Mauryans, Kushans, Afghans, Turks, British and Sikhs, as also local migrants, walked this land of the Indus-Saraswati. Amongst the above, two scenarios fit the family origin. We were either an ethnic-remix of ancient Indus-Saraswati settlers or successors of Hindus and Sikh migrants from Punjab and Jammu, who came in the wake of Ranjit Singh’s army which captured Afghanistan. The latter option is obvious, but the former cannot entirely be ruled out. An ethnic-vacuum could not have existed in Hazara before Islamic invasions of the 8th century CE?

Let me get back to recent times. It was the lure of land that seduced my father’s elder brothers to migrate from their homeland into Muzaffarabad, around the turn of 20th century. Their Parents had already passed -on. Two brothers staked claim on the land available on either banks of Kishanganga River, upstream of its junction with Jhelum. Muzaffarabad is a picturesque Shangri-La valley nestling between the hills and the river junction, at Domail. Since rivers have only two banks, for staking a claim, the youngest sibling was packed off to Srinagar for studies. The rest, as they say, is history.

-on. Two brothers staked claim on the land available on either banks of Kishanganga River, upstream of its junction with Jhelum. Muzaffarabad is a picturesque Shangri-La valley nestling between the hills and the river junction, at Domail. Since rivers have only two banks, for staking a claim, the youngest sibling was packed off to Srinagar for studies. The rest, as they say, is history.

I have already shared the story of recognition of my father’s technical-talent and royal-sponsorship to study Engineering at Benaras Hindu University (BHU), and the UK. While abroad, he was mindful of the socio-economic realities at home and resisted all distractions. He focused on gaining practical experience and in the process imbibed the spirit of English enterprise and work ethic. He came back safe and single despite temptations. And a search for a suitable-match was launched by well wishers.

S Ujagar Singh flanked by his Son, Madan,

my youngest brother and me

But an insidious maverick streak prevailed and he preferred a challenge to a secure career and family life. He felt that his qualifying as an electrical engineer was futile if his hometown remained in the dark. So he chose to electrify it through self-help and private-enterprise. He was supported by a team of spirited Sardars, who were initially hired as personal staff, but later became lifelong family friends. The last one of that vintage, S Ujagar Singh, died recently at 105, a few months after I met him in Jammu in 2014.

That intrepid team of pioneers cut the hillside to channel water, erected imported turbines and generators, set up transmission lines and commissioned the power supply, all on their own in early 1930s. It was an incredible turnkey job, all planned and executed by a young engineer and his band of karmic brothers. Amazingly, he replicated this when he was invited by Shri GB Pant, then Chief Minister of UP, to set up a micro-hydel demonstration plant in Kumaon hills. For a second time we were owners of a private power-house, except this time, he himself designed and manufactured the water-turbine. That was 1945 and the first ever in India. It was on display in the World Power Exhibition in Delhi as a state exhibit, when the visionary CM recognized its potential. The power house in Muzaffarabad drew immense attention towards my father. The Maharajas of J&K and Jodhpur had inaugurated it. His high-profile image triggered jealousy and a demand for refund of loans taken to finance the project. The upshot was that he had to sell the power house to the government, excluding the residential portion where I was born. Sadly that was also lost to Pak raiders when  they invaded Kashmir in October 1947. He joined the State Government service and moved on to other achievements. Though eventually that creative detour cost him the Chief Engineer’s job, yet he was beyond caring for power, position or possessions as long as he could follow his passion. His value of ‘work is worship’ and professional commitment have rubbed off on most of us. But there was a flipside to this single-minded focus, which I shall return to later.

they invaded Kashmir in October 1947. He joined the State Government service and moved on to other achievements. Though eventually that creative detour cost him the Chief Engineer’s job, yet he was beyond caring for power, position or possessions as long as he could follow his passion. His value of ‘work is worship’ and professional commitment have rubbed off on most of us. But there was a flipside to this single-minded focus, which I shall return to later.

Meanwhile, family pressure to settle down had kept mounting. So he took a break from work to select a bride from a short-list of suitable girls from Hazara biradari. With two grown-up girls, our Nana’s home was a natural pitstop. A direct boy-meet-girl encounter was unthinkable those days. An indirect peek through a door into the ‘zenana’ was all that was socially acceptable. Perhaps, he was thinking of a water-turbine (or an old flame in London) when he nodded approval in response to a vague target-indication towards the chosen one in a brood of girls in the next room. A cheer of celebration followed and a wedding date was set.

Our father with his two first born sons

During reception of Barat, the groom discovered that the bubbly-girl of choice was the younger-sister, not the plain-Jane proposed bride. Malicious minds muttered ‘dhoka’ but the sensible elders understood that it was visual-parallax. In the explosive Frontier culture such a mix-up was sufficient cause for loaded guns to come into action. Gussa sits very lightly on the high-noses of Frontiersmen. The family elders found a creative solution. They proposed MO-GO i.e. take both in marriage. It may seem unusual and unfair by our modern sensibilities but at the time it was acceptable to all, except perhaps the traumatised bride-to-be. But she had no voice and a lot of common-sense. Plural marriages were a norm amongst higher social classes of the time. In fact, for aristocracy it symbolised a higher status.

It was thus that the seven of us (five sons from the elder wife and a daughter and son from the younger wife) came to have twin mothers. We called them Badi and Choti Ma-jee respectively. Others may have had a problem juggling labels of mothers, masis (aunts) or step-mothers, but none of that bothered us. We were one big happy family, except when feuding.

Despina was initially shocked by this strange-scenario but found it working so well that a double mother-in-law became a welcome prospect. In case of an emotional bump, she had a handy back-up. Indeed, everything was not always free of friction. But show me one family where there is none and I will show you a liar. A unique feature here was the sisterly dimension, which enabled easy resolution of ego clashes and trivial irritants. The common bloodline and maika was a cushion. We have both witnessed the finest face of this uncommon family setting, but don’t recommend it for adoption. Sadly, one does detect some dissonance in the third generation of this family, mainly due to ignorance or perceived inheritance issue.

Is this too sanitised a picture of my childhood? Maybe it is, if viewed from a cynical perspective. Real life is, indeed, made up of pairs-of-opposites and shades-of-grey. There is no sunshine without shadows and no angel without feet-of-clay. My childhood was no exception. But I have to dig deep to recall dark-grays. It has become a fetish to blame childhood influences or incidents  for one’s own flaws, as if anyone was promised a perfect deal or destiny. Indeed, my parents were not perfect and siblings were a bunch of buffoons, servants were scoundrels and neighbours a nuisance, but overall my childhood is a beautiful bittersweet mix of warm memories. Was I specially blessed or is it just my belief? Reality is, in fact, made up of beliefs.

for one’s own flaws, as if anyone was promised a perfect deal or destiny. Indeed, my parents were not perfect and siblings were a bunch of buffoons, servants were scoundrels and neighbours a nuisance, but overall my childhood is a beautiful bittersweet mix of warm memories. Was I specially blessed or is it just my belief? Reality is, in fact, made up of beliefs.

It would diminish me in my own eyes to attribute my inabilities to rough realities of childhood. Indeed, my work-obsessed father was less inclined to tend to us (so he provided two mothers to compensate); he had a short fuse and a lethal look that was enough to set off shivers or wet-streams; and the tiger-moms were menacing in their Kali avatar. They did not pamper brattiness and believed in Spartan upbringing, Gurukul style. The tragedy was that there were no Gurus due to remote locations of my father’s postings; hydel-plants are always in way-out places.

My father and I aged 5

Consequently, I was privately tutored for many years, by under-qualified primary school teachers from nearby villages. Can I blame anybody for such deprivations? Who? In the real world no one gets a choice of parentage, places or privileges. We were taught to be happy in whatever was and learnt to count our blessings. The deprived socialization in my earlier years had a silver lining; there was less scope for comparison or undesirable contact. But it severely handicapped me in some ways, posing huge challenges later.

While my narrative may have rambled so far, let me get a bit organised now. The decade of 1937-47 was hectic at many levels. As my father got transferred, we shifted homes from Muzaffarabad to Baramulla, Jammu, Mahora (near Uri), outskirts of Srinagar and back to Jammu. Meanwhile the family had kept growing with a new member added every two years—Surinder, Santosh and Narinder (nearly overlapped), followed by Mohan, Mohinder and Madan.

Our only sister, Santosh The Six Brothers with our Father

We took long rides through verdant valleys in our English-made car (one of the few in the State), lived in huge bungalows and had hordes of servants. It was indeed a privileged and idyllic life in the salubrious setting of ‘firdaus bar ru-e zamin’ (heaven on earth). And then all the calm was rudely shattered.

Two years after WW2 ended, India was granted Independence in 1947 and in haste fractured into two. Kashmir became an instant victim and the wounded valley has been bleeding ever since. In the competing power grab for indecisive states (some say as a reaction to our police actions in Junagadh and Hyderabad), Pak-supported raiders were unleashed to invade Kashmir in October 1947. We lost our homes and properties, and both families were stranded, rendered refugees, captured and worse.

At the time, my father was in-charge of Ganderbal Division but the family was staying in Srinagar. The lifeline of the Valley through Muzaffarabad-Uri-Baramulla was severed. Essential supplies were exhausted and a strict rationing system was enforced; little fuel, salt or sugar. There was no power supply as Mahora Power House (our happy-home of many years) had been overrun. Incidentally, my eldest cousin RL Sharma (who had earlier followed my father to BHU) was in-charge. He had to take shelter with the Army during the loss and re-capture of the Power House. Later my father was summoned to assist in rehabilitation of the plant and resumption of power supply, for which he received formal commendation from his Chief on behalf of the Government.

By the end of October 1947, a shooting war was raging at the doorstep of Srinagar, not far from our residence. From the rooftop, I could see aircraft strafing enemy positions and the battle of Sheltang was fought within hearing distance. Sheikh Abdulla, the National Conference leader mobilised public support for accession to India. I marched with student processions. Meanwhile the fate of our families in Pakistan and POK was unknown, except for disturbing leaks from across the border.

In late 1948, my father was transferred to Jammu to take charge of a new division responsible for water-supply to all of Jammu province. There was no way for us to move, as Army convoys had choked all road space. Finally, the government arranged for us to be lifted in two 3-ton Lorries, as a part of the Army convoy. This was my family’s first ride with the Army; which eventually was to become a lifelong experience of two generations.

In Jammu we got a hired house to live in, which was barely adequate for the ten of us. Happily the news soon arrived that survivors of families, on both sides, were being evacuated under the aegis of Red Cross, to unknown refugee camps in Punjab, UP and Delhi. It took months of searches to trace them amongst tens of thousands that were pouring in daily.

My maternal family was assembled by Nana ji and they re-settled down in Najafgarh near Delhi. His only son, Baldev had been with us since the ’40s. My father took up full responsibility for the family of the middle brother, who had been killed by the raiders; and RL did the same for his parents and siblings. Our combined joint family strength rose to over 16. All were sheltered, raised, educated and settled by my father. Our cramped quarters resembled a railway platform, but it had all the warmth of a home. We learnt to share and co-exist in peace. Our elders taught us by example that ‘you don’t need big means but a big heart’ to do and be good!

My formal schooling started in these trying times. I was admitted in the 8th standard in Sri Ranbir High School, Jammu, just a few months before final examination. To add to my misery I came down with typhoid and was still recovering at exam-time. Despite medical advice to the contrary, a stubborn streak said ‘Go on and get it over with!’ I fluked a pass and was shocked to get a merit scholarship of Rs five per month. Friends insisted that I treat them to a movie, and I did. When I got home my mother said ‘go offer your first earning to your father and seek his blessings’. I sheepishly confessed; she admonished but gave me money, which dad doubled and gave back. This was te first exposure of my deep naiveté in matters of sensitivity and propriety; a lesson that I am still to fully learn.

It was taken for granted that I would follow the family line of engineers and that dictated all academic options. In 1949, my school decided to experiment with a golden section for gifted children, with Master Tej Ram Khajuria as the Form Master. He was a martinet but a Guru in the finest tradition of the term. And I was one of his favourites. Many years later I was Chief of Staff in that area when communal riots broke out. Curfew was imposed and the Army was deployed. I visited Masterji’s home with the Officer-In-Charge and directed that he be taken care of as befitting my Guru. They did and he was touched; but it was so small a gesture of gratitude for his immeasurable gifts to us! Till the last month of his life, in mid ’80s, he walked up to Vaishno Devi Shrine, as he had done every month of his disciplined life. By example, he had taught us the value of selfless-service, with no concern for rewards.

Kashmir University became functional in 1950 and imposed an age bar of 14 years for Matriculation. I was underage because of a couple of double-promotions in early years. All sane counsel said ‘repeat the year and you will excel next time.’ My father knew me better and was sceptical. His view was that repetition will bore and demotivate me and I will fare worse. My school had high hopes in me, so they sided with my father. My view was, of course, irrelevant.

In fact my thinking was quite ambivalent- to me it was ‘much ado about nothing’? I was sent to the education minister, who was known to my father, for seeking a special dispensation. He listened patiently and advised, ‘Son, go tell your headmaster to rectify your date of birth.” And thus my age was stretched to make me eligible. I did not disappoint the ‘punters’ and topped in Jammu province but ranked 10th overall (hard to beat the cerebral Kashmiri Pandits); not that it mattered to me as I am anything but competitive!

Next year, there was a special convocation in the Govt Gandhi Memorial Science College which I had joined. I was surprised to receive two book-awards from then Prime Minister of J&K for exceptional first-year performance. If by now you are exasperated by this one-sided portrayal of all things good, I empathise. It represents only a deceptive and skewed part profile. The other-half consists of an introverted, under-confident, awkward teen-ager, with an out-of-proportion body and challenged motor-skills; his chubby-cheeks hiding a sickly-state (annual malaria attacks, typhoid and tonsils) and an angst-ridden psyche. But why? It makes no sense? How can anyone so privileged and having such an enviable performance profile be so mixed up? That is a fair question screaming for a sensible response.

After some deep reflection, this is what I have understood. These are personal observations, tenuous but tenable. I shall use my pet metaphor. I think of creation as a networked system, a unified energy field, within which we exist as tiny bubbles. I conceptualise it as a universe of trillions of vibrating cells, each entity with its own sensors, absorbing life but responding differently to it, in their own distinct way.

Let me illustrate this with my own family’s example. My six brothers are from the same gene pool and were raised in near identical environment. Yet our individual natures and the trajectory of lives are entirely different. Clearly each one’s sensors picked up different vibrations from the common energy field of our environment. Some absorbed more positive energy and some negative, as per own programming. Let me look a little deeper into my own background, as covered, and unpack some influences:

-

Despite an exalted status later, I believe that the implicit rejection faced by my mother was palpable in her energy vibes. It contributed a degree of broodiness and fear of rejection in me, as also her bulldoggish resilience.

-

The discord between my own mental and physical abilities—the former shone and the latter shattered—thereby a contradictory complex as it were.

I could continue with my speculations but these are musings, not psychoanalysis. I considered it relevant to identify these here for understanding the dichotomies of life, the things we tend to witness only superficially as having deeper, subconscious origins.

My bipolar nature had my father concerned. One day he came across an all India gazette notification of the entrance exam to the National Defence Academy. It struck him as a eureka moment: a way to bolster an unsure young man’s confidence level, perhaps a kind of shock therapy, a make or break moment. The nearest exam centre was Delhi and it was already the last date of application. I was summoned to the principal’s office, where the PA got me to sign all the forms for something I was blissfully clueless of, at the moment. But I was thrilled at the idea of travelling to Delhi by train, my first time ever. By the same evening, my father had second thoughts; what about his dream of seeing me an engineer? His confidante, RL, came to the rescue by pointing out that Army also has engineers. He knew because his wife’s seven brothers were in the Army (Dubey family), mostly engineers and many generals.

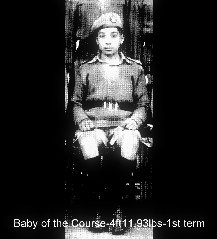

How did I negotiate the UPSC written exam and a five-day SSB Interview is a miracle beyond logic. The rigorous interview involved full time observation and assessment by a professional psychologist, a group-testing-officer and a qualified interviewing officer. I zombie-walked through all the tests. It was a touching display of innocence, complete lack of preparation, but supreme spontaneity. In fact, I was so honest as to tell them that my age was fudged and that I had little motivation for military service. I never got beyond the second obstacle, out of ten, where each fetched a point that equalled its serial number. Simply because I could not reach up to the hanging tyre. I was 4 ft 11 in tall and weighed 91 lbs. I had needed a medical certificate that someday I shall reach the cut-off of 5.2 ft, by grace of God and my genes.

How did I negotiate the UPSC written exam and a five-day SSB Interview is a miracle beyond logic. The rigorous interview involved full time observation and assessment by a professional psychologist, a group-testing-officer and a qualified interviewing officer. I zombie-walked through all the tests. It was a touching display of innocence, complete lack of preparation, but supreme spontaneity. In fact, I was so honest as to tell them that my age was fudged and that I had little motivation for military service. I never got beyond the second obstacle, out of ten, where each fetched a point that equalled its serial number. Simply because I could not reach up to the hanging tyre. I was 4 ft 11 in tall and weighed 91 lbs. I had needed a medical certificate that someday I shall reach the cut-off of 5.2 ft, by grace of God and my genes.

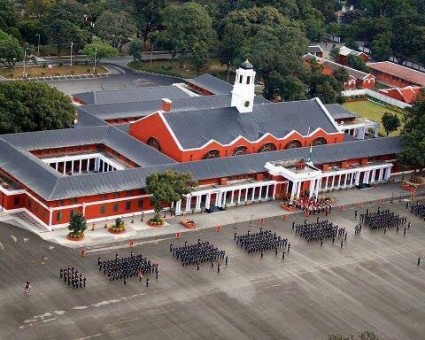

By May 1951, at barely 15, I was a cadet in the Joint Services Wing of National Defence Academy at Dehra Dun, for a four-year long course to become an officer of the Indian Army. It was like an innocent jungle boy being thrown to the wolves as raw material for the meat-grinder of the sausage-machine loftily called a Military Academy. I know, quite a melodramatic mouthful. The next four years are the most forgettable of my life; yet they formed the foundation of a richly rewarding career that has became a lifetime’s passion.

This is getting to be a schizophrenic story; a split personality all over again. To understand, you will have to empathise with my state. Fancy yourself as a sickly underdog, schooled in the back-of-beyond, thrown into a bear’s-pit with burly bullies from the best public schools (including semi-Military set-ups like RIMC, KG Schools and Dufferin). How would you react? Some others in the same boat quit and ran but I seemed to have a survivor’s spine, a bulldoggish streak.

I realised that military training was designed to ‘deconstruct’ the civilian, implant military values, and ‘reconstruct’ as a soldier. Some heavy-duty shock treatment and socio-emotional deprivation was par for the course, to defreeze old moulds. A key difference was that others had been exposed to some form of this treatment while I was a total novice . I was a midget in brawn-power and a total zero in social and sporting skills. Do challenges get any bigger?

. I was a midget in brawn-power and a total zero in social and sporting skills. Do challenges get any bigger?

I realised that this was literally a no-brainer. I had no chance of competing in certain arenas, so I instinctively adopted a survival-mode and focussed on the fields where I did have a chance. My legs may have been short but my lung-power was significant. Having been brought up outdoors and in the hills, I could run longer. In the boxing ring, I could be pluckier than my weight-plus opposition. In modern jargon this would be called SWOT, but it was simply an instinct of a fighter within the apparently pathetic little boy in the pit. And thus, for the next four years I kept my head above the water, survived and got my Commission; being competitive was neither in my nature, reach nor goal.

The special scale of rations and solid exercise had ensured that I grew to be 5 ft 10, a robust 150 lbs and graduated honourably in the middle of my batch. The President of India was pleased to grant me a lifetime Commission as a military leader in peace and war. My father proudly attended my Passing–out Parade in June 1955. He was happy that I had gained confidence; but was perplexed that I had not joined a technical Arm or Service and chosen a British Infantry Regiment, The GRENADIERS! He was disturbed at my frequent use of slang (swear-words) that he associated with the lowest of cockney class, but overall he was satisfied. My mothers were ecstatic and my handsome younger brother was so jealous as to demand immediate admission into Military or Police Academy on the strength of my father’s powerful influence. Didn’t I say that every pup in the pack is not the same?

I do not wish to give details of military training or cover anecdotes about many colourful personalities of my time in the Academy. But just for a flavour, I am including extract from my recall of those days, as written at the time of our Golden Jubilee in 2005.

*

SHADOWS AT SUNSET

This account is based on a random recall of events related to the National Defence Academy of early 50’s. Memories are like shadows, ephemeral and elusive. In the afterglow of a golden ‘sunset’, these are bound to be a mix of vague and woolly nostalgia.

It started with the first fall-in. A booming command from the high ‘Tallest on the right and shortest……’ resulted in a scramble. Everyone was sizing down the other, till humbled by reality-check! For a few at the high end it was a no-brainer. The 6ft tall Sikh (Mohinder Bal) was briefly eyeballed by a beefy batch-mate (DD Madura), but the turban ruled the right marker. At the other end there was no contest- amongst the undersized 5foot nothings- the ‘ultimate underdog’ sorted himself out. Later when the top-dogs became cadet capts/ under-officers, he held up his end, in true tradition of the ‘boy on the burning deck’!

Being last in the line for years would give anyone a complex. He too nursed raw sensitivity. But the compensation was worth it- being left out of anything seriously competitive i.e. selections based on brawn or bravado. His revenge was when others sweated, he ‘shammed’ shamelessly-that is Survivors trick No 1, which hasn’t failed him since. At worst, his tribe had to keep shouting ‘buck up-buck up Dog (later Fox) Sqn’ from the sidelines or senselessly clap at cricket matches, the favourite Sunday pastime of the then Comdt, Gen Habibullah.

The caste-structure within the corps of cadets is a reflection of the outside reality. The reasons are multi-dimensional- segmented along lines of old-school ties, entry-stream, region, and language or whatever-else. However, within a few months of the grinding-regime, most such distinctions got steam-rolled into military ethos. Many a new veneer was added, such as speaking english better than the English or Hindi like FM Cariappa, the then C in C. It is to the credit of the brilliant band of Instructors that a functional level of military leadership gets ingrained, into all-comers.

The Adjutants of the times (Kit Kataria/Whig/Rajendra Singh), were awesome figures. They were the only ones to whom the Drill RSMs (Ayling/Pearce etc) deferred politely, the rest were barked at. The Indian Drill Staff, like Sub Maj Abdul Khader, also filled the role superbly, even without the ‘swearing’ skills of the former.

Almost twenty years later one of those Adjts (by then a Brig) and I were in the 1971 War, in the same sector. He blew up on a mine on 7/8Dec and I a week later. At ALC, Pune months later, he used to encourage the amputees to march like soldiers on their new limbs. ‘Look at the mast chaal of the CO Sahib’ he would say. ‘Sir, you laid the foundation, by failing me twice in the Drill Square test’ was the prompt response. Not his fault really; no two limbs of mine worked in harmony in 1951!

Ultimately, it is the end product – the finest of young Military Leadership- crossing the Final Step into the Chetwode Building that is the most endearing and enduring memory of one’s military life.

The NDA (JSW of our times) and the IMA are the finest, ‘equal opportunity’ launch-pads of military leadership. Nothing in life is ‘equal for all’ – nothing is equal about the ‘order of merit’, the Medals or the Sword of Honour? But we were all equipped with abilities and values that enabled each one to select one’s own ‘trajectory and target’ in life and often achieve it ‘against all odds’.

Many of our Mates have crossed- over- RIP to all; to those in the queue-Om Shanti!

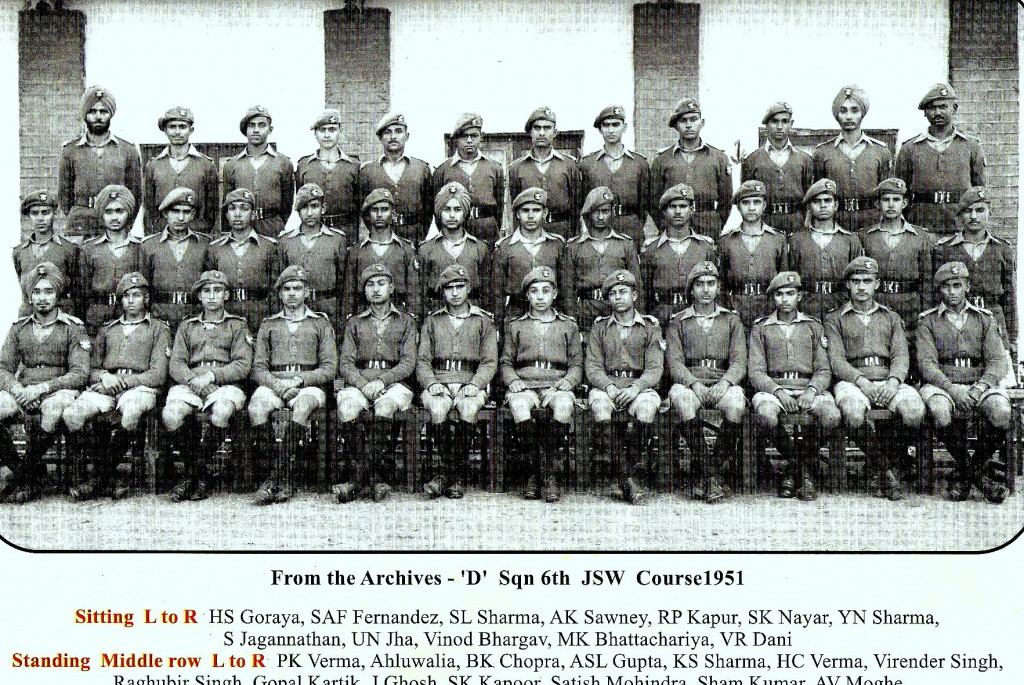

For the JSW contemporaries, a group photograph is placed below. The cadets were positioned according to heights. The tallest are standing in the last row and the shortest are seated. My place in the centre of the front row was assured. The Holy Bible says:

Blessed are the meek: for they shall inherit the earth. (Mathew 5.5)

A Footnote form the Editor

In Oct 2013, Gen YN Sharma had written a piece entitled, “Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam” in the memory of his wife. A link to that post is given below, for those who may like to read it now:

http://amolak.in/web/vasudhaiva-kutumbakam-the-universe-is-one-family/

I know this website offers quality depending articles and

additional stuff, is there any other website which gives such

information in quality?

Dear General,

Very nice piece. I thoroughly enjoyed reading it.

It took me back to my childhood. Your reference to Jhelum carried me to Khushab on its banks,

Where I was born, but never lived, and yet, yearn to visit it. Surjit, who is from Sargodha, and I, even made plans

To visit these places, but somehow, it never worked out. Insha Allah some day !!!

And you could teach the English a thing or two about their language.

I have hung up my boots but stay on as non executive Director of Endolite.

Trust you are keeping well and your prosthesis is comfortable.

Would you like Sweta from Hyderabad Centre to visit you and carry out a check?

With warm regards.

VK

Where I was born, but never lived,??????

But you must have at least for a week

unless they ushered you away in a plane straightaway

Thanks nice knowing you

My THANX to Gen Surjit for bringing to light this Story, which one would have never seen otherwise.

Having intimately known Gen Yogi Sharna as a Lovable- Trusted senior in the Regiment, it is only now that we have come to know of his ‘ Historic’ background & Spartan upbringing — inculcating in him the values which we ourselves in the Regt have had the Good fortune to learn from him.

Thank You, Gen Yogi, Sir, for the ‘ Lead’ that YOU have given us in almost all spheres of our Service Life — & even thereafter.

While others may ‘RIP’, may you continue to live Long so that you remain there as a ‘ Beacon’ for us.

Thanx for setting examples for us to emulate — including the writing of our own past.

Maj Gen Aditya Jaini

It is very insparing, to read life of my first Commanding Officer. He is THE BEST officer, I ever came across.

Makes very nice reading.

Thanks and regards,

Surendra

Thank you Sir.

This makes great reading.

regards,

Hari Kumar

Thanks, Surjit

I had met Gen Yogi Sharma quite often when he was Xll Corps Cdr in Jodhpur, when I was a small fry Air 1, at HQ SWAC there, in 1990-92. His wife had an ‘Athenian’ connection, if I recall right!

Impressive, both as a man & as a Cdr!

Inoo

Hi Surjit

Thanks a lot . Having served with Gen Yogi Sharma, it was pleasure to read the story , though one knew most of the basis facts , there are many which were not known to us.

He was great soldier and she was a very hospitable person Their daughter was also growing into a young ladyat Mhow and at Wellington . I remember my last dinner with the family at Belgaum , where i had gone too visit my brother Though I had by then retired , he insisted that we have dinner with the family.

Thanks

Surindar

Sir,

Many years ago, when Khushwant was with the ‘Illustrated Weekly’ he was approached by a lady who had written the story of her dutiful son, whom she had brought up very well. The boy did well in studies, and passed all examinations without using unfair means. He did a stint abroad, but even in the USA, he never spoke to any young lady. On return, he married the girl of the parents’ choice and joined the family business. Needless to say, he was a very caring son.

Old Khushwant turned to her and said,

“Madam, this tale is fit to be recounted in a temple or gurudwara. If I edit it for the “Weekly” it may not be able to cover a complete stamp… not even a revenue stamp!”

The story told in this post would have been selected. It has enough twists and turns to hold the reader.

Surjit

Thanks for the ‘uninspiring’ story-no fireworks? Re-read and discovered some hidden lessons:-

- SSBs sucked, then as now- look at the venom about ‘generals’ on net/social media!

- promotion system is sick- how else low-calibre keeps rising?

- no appetite for change-status quoism- revamp institutes of learning/consultancy that are regurgitating!

- who can say quality of intake declining after reading this. Take it off till 7 CPC/OROP!

POSITIVE THOUGHT- INCORPORATE NADI READERS in lieu of above for better results- Napoleon said ‘Give me lucky generals not good’!

This is a good start you give,Dear General,

I shall some day post my life story

”Riches to RAGS and Return”

Colls

life is a flowing river

it meanders

as it reaches the estuary

to cease

BEING!

An interesting story. A lot of history is covered here. Thank you, sir, for writing about your life and times.