From my archives

Recently, I read a ‘middle’ article written by Rashmi Oberoi in a newspaper in which the author recounted an incident which was very similar to my own experience, forty odd years ago. Way back, in 1972, I wrote a story based on what I saw in a hospital. I was able to lay hands on it, and when I read it, I found that the observation which I made all those years ago, is still valid. The net outcome of what happens in the courts of law has a lot of similarity with what the doctors do to us. I am tempted to share this little story with you.

I have taken the liberty of inserting Rashmi’s story at the end.

*

Crime, trial, verdict and sentence

There is one more institution where people are tried and judgments delivered: the hospital. Men and women are brought in for alleged offences such as enlarged livers, malfunctioning hearts, broken bones or infected lungs. The ‘accused’ persons are tried by a jury of learned men of medicine. X-ray pictures; blood and urine reports; ECG curves and temperature records appear as witnesses. Although the atmosphere smells of antiseptics, and the place is a great deal less noisy than a court of law, yet the outcome is remarkably similar.

The sentences vary between a term in the hospital wards to physical decapitation of an organ or limb. Capital punishments are also awarded, but the execution is less dramatic, though often, much more painful and torturous. I also observed that no matter how big or powerful a man, he has scant control on his own body organs. The President of the United States controls the destiny of all countries on the earth, and can order mass destruction of towns or even nations; but he has no power to regulate the functioning of his own kidneys or liver!

This is the way I regarded the Hospital when I was admitted there for a minor surgical procedure in March 1972. The war was, then, a recent event and its hangover persisted. The surgical ward was full of mutilated soldiers. Many of them had come from distant places and, therefore, received no visitors. Compared to them, my own suffering was so slight that during the visiting hours, my wife and I spent most of our time with other patients. This is a tale of two of the several friends we made during those days. They had nothing in common, except that in their hours of tribulation, they were together in the same hospital. That and the fact that they were both very nice people. Men whom it is so easy to get to like.

Major Kumar attracted our attention for two reasons; his extremely good looks and his utterly aloof nature. He used to spend the entire evening sitting all by himself, with a book in hand. I was told that he was in the promotion zone and that he had come to the hospital for a routine check-up.

One day, we saw that Kumar had parted company with his book also. Silently, he sat on a garden chair, staring idly at the infinite sky. There was a vacant look in his eyes. My wife suggested that we go and meet him.

As we got nearer, he got up and wished the lady. “I am Major Kumar,” he said, with his hands folded in greeting.

I told him my name and we shook hands. He went in and pulled out two chairs.

“What has happened to you?” My wife asked.

“Nothing… Nothing at all. Got fed up with the unit routine, and this is a nice place to rest for a change,” he said. “The best hotel in town, you know!”

But having said that, he broke into a cough which took quite some time to settle. We fell silent. Illness is an offence and we in the service do not own up to it easily. It is bad manners to probe anyone on this subject. But apparently, my young wife was not in her best social form that evening, when she said, “The cough seemed bad. You must get it checked up properly. My great-aunt used to suffer like that and it turned out to be bronchitis.”

“That is what I am here for,” Major Kumar confessed. “I do not know much about medicine, but they tell me that I have an infection of the upper respiratory organs.” And he again took in a deep breath.

I noticed another patient on a chair close to us, just sitting and blowing away rings of cigarette smoke. Every few minutes, Major Kumar looked balefully at him. In fact, every time he turned his eyes towards the smoker, a ravenous expression would appear on his otherwise serene face.

“Where are you posted?” my wife broke the silence. “I mean, where is your unit? Is your wife not here?”

“My unit is in J&K. I am from the Punjab Regiment and I am not married.” He answered all her questions in the same breath, and then quipped, “Wasn’t as lucky as your husband.”

“He is going to take over a battalion as soon as he leaves the hospital, darling,” I said. “Very soon he will be the Commanding Officer of an elite unit.”

“Ah yes!” he sighed. “CO, indeed. Every Army Officer aspires to command his battalion or regiment one day. But there is many a slip between the cup and the lip.”

With grave eyes, he looked at his fingers. They were dark brown with nicotine, an evidence of the number of cigarettes they had held for their master. It was obvious that he had been forbidden to smoke for reasons of health.

“Life is unpredictable, you know,” he continued his monologue. “Just when you begin to feel that you have reached somewhere, the ground slips from under your feet. You find that you are exactly where you began. Not an inch ahead!”

My wife was not listening. I knew her mind was working somewhere else.

“Punjab Regiment, you said. Isn’t it?” she interrupted him right in the middle of the sentence. “Is your Regimental Centre in Meerut?”

“Yes, it is,” Kumar said. “Meerut is our hometown.”

“I like your Officers’ Mess,” my wife said. “A few years ago, my father was posted in Meerut. He knew your Centre Commandant. I have attended a couple of parties in your mess.”

“What did you like the most in our mess?” Major Kumar asked. I could see that he liked the subject. Even I found it livelier than the morose philosophy of life.

“There was a painting at the entrance. I think it was a masterpiece. What was it called?” And then she answered the question herself, “Yes, I remember. The silver plate beneath it read, ‘The Aftermath of War‘ by Brijesh Kumar. Do you know the officer who has done it?”

“I am Brijesh. Brijesh Kumar.” Suddenly, his eyes lit up. “Are you referring to the picture which contains a lot of rubble?”

“Oh, so it is you! The painting is exquisite, and I don’t think it has just got rubble in it. It is an expression of the grim realities of life.”

“You remember so much of it!” a gratified Brijesh Kumar exclaimed. The look on his face had changed completely. He seemed alert and cheerful.

“Yes. A good bit,” my wife said. “There was a hut in the lower left corner, a heap of waste fragments of broken down houses in the foreground. Rubble, as you said, rubble painted in the most depressing colors I have ever seen. In the corner, near the hut, there were two figures: an old woman with a wrinkled, tired face, and a toddler wearing a radiant, innocent look. I used to marvel at the contrast in their expressions. And then in the upper right corner there was the soft, pink sun. One half above the horizon and the other half hidden beneath. I always wondered whether it was a rising sun or a setting one. Tell me, did you intend to paint dusk or dawn?”

Eager, curious and impatient, she was a child at that moment. She could have gone on like that. A painter of sorts herself, she is a great fan of all good artists.

“I don’t know,” Major Kumar said. “With your words you have put more beauty into it than I had done with the brush. Was it Tagore who said, ‘Beauty lies in the eyes of the beholder’? How true!”

“Yes, I know,” my wife said. “You must have left it to the viewer. It could be either: depending upon the mood of the person who sees it. Shall I tell you? When I looked at the child, I thought it was dawn. The rays from sun appeared to symbolize hope of a brighter tomorrow. But when my eyes fell on the old lady, the entire complexion of the picture changed: the colors of the rays of the sun lost their brightness and turned into a ghastly reminder of the day that had gone by, something that had been lost.” She became emotional.

“Come, now,” I interrupted. “You have almost composed a poem on the painting!”

Brijesh seemed to realize that enough had been spoken about the painting. Deftly, he changed the topic, “It is getting cool. Shall we move in?”

“Yes,” I said, and turned to my wife, “I think it is time for you to leave. You have a long way to go. If it becomes dark, I will feel anxious for you.”

”Yes, I think so too,” my wife said. Then we said the parting words, promised to see Major Kumar again and came back to my ward.

A new patient had shifted on the bed opposite mine. The nursing assistants were helping him to turn his side. He seemed to be badly off.

I went up to him and wished him. He was awake, but did not respond to my “Good evening”. He just blinked his eyes but made no motion or gesture to suggest that he knew what was happening around. A nursing assistant explained the situation.

Lieutenant PC Badola. That was his name. He had suffered a head injury in a road accident in October 1971,two months before the war. Since then, he had been in a state of coma. For six whole months he had been that way. All through that long time, he had been kept in the ‘Intensive Care Unit’ of the hospital. They had been feeding him through a Ryle’s tube. At regular intervals the hospital staff changed his side on the bed, to avoid bedsores.

Alive, and yet dead – a vegetable. That was his condition. Men of medicine were keeping him alive in the hope that, some day, he would regain his consciousness. It was a pathetic sight, and from the next day onwards, whenever my wife looked towards him, her eyes became moist.

I knew that we would be seeing more of Major Kumar. I also knew that he would look forward to meeting us, particularly my wife, for, I do not yet know a man who is not flattered by kind words spoken by a young lady.

We met him the very next day. From the window of my room, I saw that Brijesh had got three chairs laid out in the lawn opposite his ward. He was sitting on one of them and was quite obviously waiting for us. We did not disappoint him. He was quite cheerful that day. “You know, Mrs. Chawla.” he said, “I have not got married so far because I always thought that marriage would rob me of my independence, my freedom. I do not like my freedom taken away. I am impulsive. And so I dislike being told what to do and when. I have always acted on impulse and so have done . . . smoking, drinking, painting and reading. I have always done these things passionately and compulsively.”

We just listened. He was speaking so passionately that we did not feel like disturbing him. But suddenly he stopped, let out a deep breath and said, “On seeing the two of you together, I have decided to get married. I have begun to think that marriage is worth the sacrifice involved.”

“It is, indeed,” I agreed. “You should get married, Sir. It brings fulfillment to life.”

At this stage, his cough broke out, spluttering, and choking. He made a valiant effort to suppress it, but that made his cheeks go red to the ears. He muttered a faint “Excuse me” and rushed into his room.

We left him and came back to our ward. The attendants were laboring on Lieutenant Parmeshwar Chand Badola. He had contracted some infection and was running a mild temperature. The assistants were trying to administer medicines through the tube.

These two, Brijesh Kumar and Badola, became a part of our lives. Neither had any visitors, and so my wife took it upon herself to look after their welfare. This much, and more. She made friends with the matron and got to know their detailed clinical condition.

Brijesh’s was a case of suspected cancer; cancer of the lungs. A result of long and heavy smoking. A portion of his infected tissues had been sent to the All-India Institute of Medical Sciences for biopsy. The result was expected in couple of days.

Badola had a head injury. There was no fracture but it was feared that it was a case of cerebral hemorrhage. If the wound inside the skull did not heal, he was doomed to die there itself. But it was difficult to tell either way until he recovered his senses. There were no known means of determining the extent of damage to the brain. A neurosurgeon would see him when and if he regained his consciousness and assess his condition. For the first three months, his mother and brothers were in Delhi to look after him; but then, one by one, they had gone away. They could not afford the cost of living in the capital. Now, he was all alone, and entirely at the mercy of the hospital staff. He had no visitors.

Three days later, the biopsy findings came in. Brijesh’s cancer was confirmed. It was in the terminal stage. He had suffered for over two years but had kept it to himself. My wife was told by the nurse, in the strictest confidence, to keep this information to herself.

I have not seen my wife cry the way she did that day. As if someone who was her very own had been awarded the death penalty. But courageous as she is, she soon regained her composure and equanimity.”We must go and see him,” she said. “He is our guest now. We owe it to him.”

He was not sitting outside that day. We went to his room. He was there, but not alone. His erstwhile batman was with him, squatting on the floor in front of him. They were both drinking rum and Brijesh had a packet of cigarettes on the bedside table. The ash-tray was full to its brim.

At once we knew that the secret had not been kept by the hospital staff. Apparently, Brijesh knew the outcome of his verdict and he had lifted his embargo on tobacco and alcohol.

My wife saw all this from a window. I do not know whether Brijesh had seen her, but she rushed back to tell me what she had seen. We did not have the courage to go in.

A nursing sister was also standing there, looking on helplessly. Hospital rules do not permit drinking alcohol in the wards. But apparently, she did not have the heart to say anything to Brijesh. The next day, we heard that Brijesh had refused to be shifted to Poona or Bombay for expert treatment of cancer.

“Give me any damned medical category you want,” he told the Commandant of the Hospital, “but send me back to my battalion. I will stay there with my men until I can move my limbs. There is no one else in the world I care for. I have nobody whom I can call my own.”

And then, they say, Brijesh broke down. He wept like a little child.

Badola regained his senses while I was still there. For a couple of days he was a little dopey, but then, slowly, he recovered his memory and he could recount the story of his life with reasonable clarity.

Catastrophe struck when the neurosurgeon tested the reaction of his appendages. It seems that the limbs on the left side reacted to the beating of the surgeon’s hammer much less than the right ones. The verdict was that his left side was paralyzed. The authorities on the subject predicted that the process of decay would be a slow one, even though there was no immediate danger to his life. Only, his movements would be restricted, and at a later stage his speech could be affected. It was also doubtful whether he would ever be able to walk about.

I thought the verdict on Parmeshwar Chand Badola was more callous. He had been, honourably, condemned to LIVE!

Mirza Ghalib has said,

Qaid-e-Hayaat o Band-e-Gham,

Asl Mein Dono Ek Hain

Maut Se Pehlre Aadmi

Gum Se Nijaat Paye Kyon?

This prison called life and the sorrow captive in it,

In reality are one and the same

Before the very end (death),

How can then one get free from it?

A Postscript

As I was going through the story last night, I was reminded of something which I had read in a book by Lobsang Rampa, nearly fifty years ago. In that, he said something which made eminent sense to me. He said that in Tibet, when someone committed a crime or offence, he was sent to the jail, but no specific period was specified. They believed that the person was ‘mentally sick’ and needed to be ‘reformed’. And as soon as the prison authorities considered him to be fit enough to live with his folks, he was sent back, just as we discharge patients from the hospital. And in the same breath, Lobsang Rampa said, “All prisoners are permitted to take a walk through the streets of the town in the evening, and the people are taught to look at them with a kindly eye. This is because we believe that all of us are culpable, and would be in prison, had we been caught!”

*

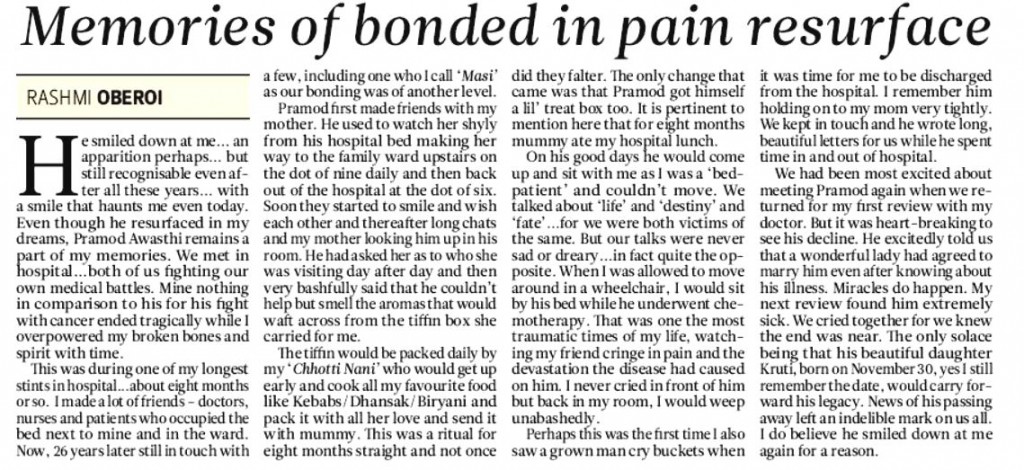

Rashmi Oberoi’s middle article which prompted me to pull this story out of my archives is given below. Note the striking similarity with the above tale.

See http://www.zocalopublicsquare.org/2011/11/30/how-doctors-die/ideas/nexus/

Dear Sir,

By reading this I was transported back to the R&R hospital and MH Kirkee where i spent 23 months.Seen may colleagues ;officers and OR from all three services with no hope for future,yet continuing life.Many have left this world and many are in a bad state due to kidney problems,bedsore,constipation,spasm and cramps,yet living with courage and determination.Hospital is a virtual prison especially with 100% disability ,with no sensation or motor movement and being assisted even for turning on the bed.Many wish death than the miserable life with total dependence.You are not only a burden to yourself but to your kith and kin too.How long can one be cared for?.Some are fighting it out with hope against all odds!.

Ganga,

I can ‘feel’ what your words convey. An Urdu poet has said,

“Zindagi se badi sazaa hi nahin

Aur kya jurm yeh pataa hi nahin”

(No punishment is more severe than life

And we never get to know what crime we have committed!)

Regards,

Surjit

Dear Sir,

By reading this I was transported back to the R&R hospital and MH Kirkee where i spent 23 months.Seen may colleagues ;officers and OR from all three services with no hope for future,yet continuing life.Many have left this world and many are in a bad state due to kidney problems,bedsore,constipation,spasm and cramps,yet living with courage and determination.Hospital is a virtual prison especially with 100% disability ,with no sensation or motor movement and being assisted even for turning on the bed.Many wish death than the miserable life with total dependence.You are not only a burden to yourself but to your kith and kin too.How long can one be cared for?.Some are fighting it out with hope against all odds!.

Wow Uncle…

So similar…

I shall share it on FB.

Rashmi

Rashmi,

It is my firm conviction that your reactions to the harsh facets of life are similar to mine. Recently I heard a ‘ghazal’ in which one couplet says,

“Zindagi ko karib se dekho

Iska chehra tumhe rula dega!

I dread a visit to hospitals. It touches a sensitive chord in my heart.

Best wishes,

Surjit

Thanks sir for sharing. Very touching.

Satti Chahal

Dear Surjit

I was touched by the theme. Enjoyed reading it thoroughly.

Naresh

Thanks.

Anil-Sunita

Excellent simili

Venki,

Thanks.

You doctors have a lot in common with the lawyers!

Surjit

Dear General,

I have read through your story and found it very real with emotional touch at appropriate places. It is a difficult job but you have done it well perhaps because you felt it as you wrote it.

My complements.

With regards,

Yours sincerely,

Ashok

P.S. I regret for not having completed the task that I promised I will undertake – the young IPS fellow and his articles – but I will do it soon enough. Kindly bear with me.

Coomar,

I can wait. Age has taught me patience!

Surjit

Very touching. But it depicts life, very truly!

TUSI GREAT HO…

Gagi

Thanks, Sir.

It was a very touching recall of the past.

I have spent about 36+ yrs in an Army Org ( In civilian capacity ) & has visited 100 + units in peace & field for Insp, Trials & Defect investigation of SPL Vehs Ex EE countries from 1972 to 2008.

I have seen their life quite closely & have deep regards for them.Almost all of my officers were

Service officers ( EME ) & always blessed / backed me in my service life. I am in contact with many of them. It is some of their mail that you got my mail ID & responded first , for which I am thankful to you.( I think it was perhaps late Maj Gen VK Malhotra OR Maj Gen KP Deswal )

With warm regards ——– Prakash

Dear Prakash,

Thanks.

You are a part of the EME family! VK Malhotra and Gen Deshwal are both very dear to me.

Where are you settled? And I am sanguine that you are gainfully employed.

Surjit

Very touching indeed.Thanks for sharing.

Parminder

Life’s Like That.

Dear Surjit,

A brilliant story. Time to write a sequel to this. Something like

“Delighted to live”. I give the name, you write the story.

Surinder

Dear Gen Surjit, a very sad but touching story. Reading through it I was transported to the hospital ward and felt as if I was talking to Maj Kumar.Looking fwd to more stories from you. GSB

Dear General,

You have made my day!

Whenever I think of Lt Badola, my eyes become moist, even now. He looked so helpless, so lonely…and yet, he was hoping against hope that he would be up and about soon.

I suppose life is like that!

Surjit

Surinder,

Dear Jhaiji used to tell us a ‘nikki jihi gal’ She told us about a lady, who gave a sewing needle to her daughter, and told her, “I am giving this to you…and in due course, I will also give you a sewing machine!”

The heading you have given is analogous to the needle.

And I will work on it. Who knows, it will germinate into a story one day. You are the one who thought that the trust should have its own website. It has got one, and hopefully we will expand it.

Surjit